A new theory of the origin of the terrestrial planets—that Jupiter’s gravity pulled them inward from the outer solar system—solves longstanding scientific riddles and offers a rich agenda for further investigation.

A new theory of the origin of the terrestrial planets—that Jupiter’s gravity pulled them inward from the outer solar system—solves longstanding scientific riddles and offers a rich agenda for further investigation.

Jupiter’s Pull

An array of new evidence helps us correct with a Revised Venus Theory the explanation by Immanuel Velikovsky of ancient myths that Venus emerged from Zeus/Jupiter. Venus was actually pulled from the outer solar system by the gravity of Jupiter and passed near the gas giant, thereby heating up from the tidal force caused by Jupiter’s immense gravitational field, losing its ice, gaining a comet tail, and being steered into the inner solar system. All this seems to have happened around 2525 BC when Venus first began to be depicted as a comet by the ancients.1

In the early years of the solar system, Jupiter’s gravitational field is generally thought to have directed many planetesimals into orbits on the fringes of the solar system but also some into the inner solar system. So we can posit that all the terrestrial planets were orbiting outside of Jupiter and then (with the exception of Venus) were pulled by Jupiter into the inner solar system billions of years ago.2

While Jupiter’s gravitational pull ensures that no large object can remain for more than perhaps 30 million years in the Jupiter-Saturn slot,3 rapid accretion in the early solar system would have permitted Earth quickly to attain a high mass by impacts with planetesimals. Meanwhile, we know that the regions around the outer planets are exceptionally clear of debris, suggesting that it was all swept up long ago by Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. But there is one exception.

The slot between Saturn and Uranus appears to contain zones where planetesimals could have orbited without being vacuumed up into these large planets. However, this area is also very clear of debris. One explanation would be that this was the slot of Venus, which cleaned up these objects until, around 2525 BC, Saturn’s or Jupiter’s gravitational pull or some other cause steered it in the direction of Jupiter, which directed it into the inner solar system.

Various features of Venus—that its surface is so hot, that it appears old yet has a new surface, that it contains 150 times as much deuterium relative to hydrogen compared to Earth (a sign of a large amount of water in the past), that it seems to have a residual tail (the famous but dwindling Black  Drop), that it rotates very slowly in a retrograde direction as if after tidal locking to Jupiter, and that its atmosphere is super-rotating at more than 50 times the speed of the planet—match the explanation that it was pulled by Jupiter’s gravity into the inner solar system. In ancient iconography, Venus was depicted as ovoid, as in this portrait of the Egyptian Venus goddess Sekhmet, consistent with being stretched by Jupiter’s gravity.

Drop), that it rotates very slowly in a retrograde direction as if after tidal locking to Jupiter, and that its atmosphere is super-rotating at more than 50 times the speed of the planet—match the explanation that it was pulled by Jupiter’s gravity into the inner solar system. In ancient iconography, Venus was depicted as ovoid, as in this portrait of the Egyptian Venus goddess Sekhmet, consistent with being stretched by Jupiter’s gravity.

The ancient Greek myth of pregnant Metis has Zeus (Jupiter) turn her into a fly that zips into his mouth and gives birth to Athena inside him. Then another myth has Athena spring from the head of Zeus (her name was originally A Fena, meaning The Phoenician Lady, aka Venus, the brilliant rising Morning Star/Comet). New evidence from China, Egypt, Armenia, and Mesoamerica shows how ancient peoples worldwide responded to Comet Venus’ terrifying, catastrophic approaches to Earth.

Thus it seems fair to conclude that the Venus/Velikovsky controversy has found a satisfactory solution at last.

Circularization of Orbits

All four terrestrial planets, and the Earth’s Moon as well, presumably had highly eccentric orbits when they first entered the inner solar system. Curiously, Mercury (21% eccentricity) and Mars (9%; varies from 0 to 14%) still possess the most eccentric orbits of the eight planets, but Earth (<2%) and Venus (<1%) have very circular ones. The requirement for a speedy circularization of the orbit of Venus has been a major target of critics of ancient accounts and evidence that suggest that it entered the inner solar system shortly before 2500 BC.

What properties do Earth and Venus share that would have led their orbits to become circular?

First, the Earth has oceans, and both planets have thick atmospheres, that would have created plasticity that reduced the eccentricity of their orbits.4 Second, both were very hot in their early years in the inner solar system (on the origin of Earth in the Outer Solar System, see below), and this heat would have increased their plasticity and hence made them more pliant to the gravitational pull of the Sun, which would have tended to render their orbits more circular. Third, the giant cometary tail of Venus and the Earth’s Moon would have in parallel fashion tended to lessen the eccentricity. Fourth, Earth and Venus both interacted with other planets in ways that would have made their orbits more circular. Specifically, each of more than 30 passages of Venus near Earth every 52 years between ~2525 BC and ~700 BC would have, via gravitational tugging, bent Venus’ orbit and made it ever more circular. Earth also seems to have interacted repeatedly with Mars in prehistoric times. Fifth, in ancient times Venus had a markedly ovoid shape.5 Comet Venus appears to have moved at times in the direction of its major axis, and this would have added to its length and malleability under gravitational forces and hence its tendency to circularize its orbit. Having lost Mars (see below), Earth, too, would initially have had a less-than-uniformly spherical shape and thus might have been less resistant to circularization of orbit. Sixth, the electromagnetic force might have played a role, though in what manner and to what extent need to be modeled, including whether the tails formed dusty plasmas.

In fact, scientists generally recognize that rapid circularization must occur in the presumably originally highly elliptical orbits of short-term comets that end up with circular orbits, otherwise they would lose their material when interacting closely with the Sun on hundreds or thousands of highly elliptical passes. Comet Venus evidently resembled such comets.6

A discussion of the orbits of planetesimals concludes: “Most close encounters between planetesimals did not lead to a collision, but bodies often pass close enough for their mutual gravitational tug to change their orbits. Statistical studies show that after many such close encounters, high-mass bodies tend to acquire circular, coplanar orbits.”7

Comet Moon

In keeping with OSSO, one can see a solution to the puzzle of the origin of the Earth-Moon system that makes sense of the capture theory, often thought implausible because of tight parameters of velocity and starting position that the Moon would need to fulfill. Of course, the various satellites in retrograde orbit around the outer planets suggest that capture is not improbable at all.

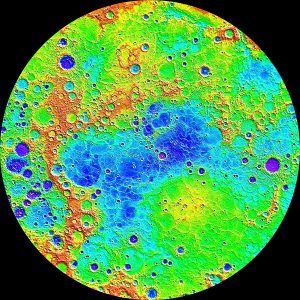

Initially, a smallish protoplanet (“Merculuna”), which had come from an orbit close to the original orbit of Earth outside of Jupiter (making sense of the close match between the oxygen ratios of Earth and Moon), would have heated up tremendously on its passage past the gas giant. The gravitational force exerted by Jupiter would have pulled a smaller molten part out of the larger part. The larger part, containing the main iron core, would have continued on into the inner solar system as Mercury. Its magnetic field was shifted roughly 20% of its radius to the north of its equator, suggesting that Mercury had lost a large component (the Moon) from its north pole (this NASA image of Mercury’s northern hemisphere shows the depressed polar region in blue).

the north of its equator, suggesting that Mercury had lost a large component (the Moon) from its north pole (this NASA image of Mercury’s northern hemisphere shows the depressed polar region in blue).

Around the north pole are volcanic plains up to 2-3 kilometers thick, forming 6 percent of Mercury’s surface, the lowest part of the planet. The lava appears to have gushed out of vents up to 25 km long. A large, highly reflective area in a deep depression at the pole strongly suggests water ice—and this water ice may be aboriginal, too much to be conveyed by comets. Mercury’s south pole correspondingly has a small depressed area at its center surrounded by what appear to be faint concentric rings, consistent with an area of antipodal disruption that had been sucked inward as the Moon was pulling free from the north pole region. The loss of the Moon’s mass caused Mercury to shrink, leaving long cliffs or scarps up to 3 kilometers high as wrinkles ranging from north to south. Cooling of Mercury’s interior contributed to the shrinkage.

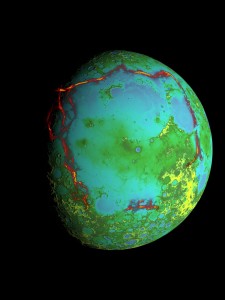

The other piece of Merculuna, composed of a small amount of iron 8 but mainly of silicate rock, with most of the volatiles in its crust and upper mantle, including water, burned away by the heat, and with a long comet tail of rock and dust shed from its surface, would also have escaped Jupiter and proceeded into the inner solar system. This partly molten Comet Moon would have been malleable and prone to becoming entangled with the gravitational field of Earth because the highly elliptical orbits of both created many occasions for interaction. Its separation  from Mercury would have left it skewed both in shape and in elemental distribution. The giant Oceanus Procellarum on the near side on this NASA image is the scar left by the separation event. The rectangular shape of the gravity anomaly surrounding it (here marked in red) sharply distinguishes it from impact craters. Its size roughly approximates the size of the depressed area around Mercury’s north pole. Consistent with this, the evidence of higher heating found on the surface and upper mantle of the near side can be interpreted as the consequence of the near side having been the highest energy intensity location as the Moon was torn from Mercury during the separation event. The unusually high magnetic field around the Reiner Gamma Formation within the Oceanus Procellarum is a remnant of the original magnetic field of Merculuna and should have an intensity roughly matching that of the remanent magnetism of Mercury.

from Mercury would have left it skewed both in shape and in elemental distribution. The giant Oceanus Procellarum on the near side on this NASA image is the scar left by the separation event. The rectangular shape of the gravity anomaly surrounding it (here marked in red) sharply distinguishes it from impact craters. Its size roughly approximates the size of the depressed area around Mercury’s north pole. Consistent with this, the evidence of higher heating found on the surface and upper mantle of the near side can be interpreted as the consequence of the near side having been the highest energy intensity location as the Moon was torn from Mercury during the separation event. The unusually high magnetic field around the Reiner Gamma Formation within the Oceanus Procellarum is a remnant of the original magnetic field of Merculuna and should have an intensity roughly matching that of the remanent magnetism of Mercury.

Separated from Mercury and braked by Jupiter’s gravity, the Moon would have roughly followed the trajectory of Earth and ended up in very approximately the same orbit as Earth, in keeping with Kepler’s Third Law and the orbits’ eccentricity, noted above. Thus the Moon shared with Earth the same niche of origin, a similar trajectory, roughly matching chemistry, the same braking mechanism, and a similar velocity. The tight parameters of the old Capture theory would give way to generous parameters within which Comet Moon—exceedingly responsive to tidal forces—could have readily fit; and, perhaps after a number of misses, it would end up orbiting the Earth in an initially highly eccentric but gradually circularizing orbit, slowly cooling and losing its comet tail yet retaining the memory of its heated state in a rather small molten outer core and an extremely hot, dense, solid inner core. (Mercury possesses a molten core.9) This scenario overcomes the main objection to the Capture theory by identifying Jupiter’s gravity as the appropriate braking mechanism required to slow the Moon down to the same velocity as Earth’s.10 This scenario of a Moon with a highly eccentric orbit upon capture provides a nice match with data regarding the Moon’s three principal moments of inertia, which are not consistent with the Giant Impact theory.11 It also suggests that many of the solar system’s moons were captured comets.

The finding that lunar melt inclusions protected by crystals contain fairly high levels of water as well as other volatiles 12 seems consistent with this scenario of high, steady heat that caused the outgassing of almost all volatiles down to 500 km depth except those in the crystals, whereas it seems very inconsistent with the Giant Impact hypothesis of the origin of the Moon, which entails an ultra-high energy event that would presumably have melted the crystals. As the authors of the lunar melt inclusion article note, their evidence rules out the arrival of water after the heating that the crystals withstood; the water was preexisting—a good match with an origin in an icy Merculuna in the outer solar system.

In effect, Comet Moon was hot enough to lose surface matter that then formed a tail, to outgas almost all volatiles down to 500 km, and to be sufficiently malleable that the Earth’s gravitational field could capture it; but not so hot as to destroy the crystals that encapsulated volatiles or completely to smooth over the indented surface where the near side had been torn apart from Mercury. The Moon’s top 500 km thus were tidally heated to a high degree during the peripheral passage of Jupiter, then cooled, while the core remained exceptionally hot as a memento of the high-energy separation from Mercury.

The theory also provides explanations of Mercury’s molten core; relatively high orbital eccentricity; very high iron content; and skewed distribution of magnetic field so that the northern hemisphere has a higher magnetic field,13 consistent with a separation event in which Jupiter’s gravitational field pulled material from its north pole region. It also fits the presence of many volatile elements on Mercury’s surface that should have been dispersed by solar heating; in particular, the potassium:thorium ratio suggests an origin in a cooler place farther from the Sun.14 Instead of two ad hoc giant impacts with complicated post-impact scenarios, a single separation event integral to OSSO during the peripheral passage of Jupiter would account for the distinctive features of the Moon and Mercury.

Because Mercury has 4.5 times the mass of the Moon, it would have been more resistant to heating up during the peripheral passage of Jupiter than the Moon was. Mercury would also have been more resistant to Jupiter’s gravitational pull after separation and so might have followed a slightly more distant trajectory from Jupiter. The consequently relatively lower (but still high) temperature could explain why Mercury has much higher levels of potassium and sulfur, which presumably would have been lost by the hot Comet Moon. Data from the MESSENGER orbiter are very consistent with a Mercury-Moon separation event whereas they undermine competing hypotheses such as a giant impact that caused Mercury to lose a putative original thick coating of silicate rock.15

The Moon possesses remanent high-intensity paleomagnetism seemingly derived from a dynamo; and its intensity surpasses the capacity of the small lunar core to generate a field.16 These characteristics are very plausibly the consequences of a Merculuna dynamo that the Moon lost upon separation about 3.95 billion years ago (it is not clear, however, how the Moon’s magnetic field remained at a high level for many millions of years thereafter, suggesting that an unsuspected mechanism generated the field). For some time, the Moon and Mercury, on highly elliptical orbits, passed repeatedly through the asteroid belt, accounting for their similarly heavily cratered surfaces and obviating the need for the Late Heavy Bombardment hypothesis. Then, before the Moon cooled and lost plasticity as well as perhaps its comet tail, it was captured by Earth. This dating contradicts the Giant Impact hypothesis of the Moon’s origin, which places that putative event many hundreds of millions of years earlier. Supporting this interpretation is evidence from zircons that Earth’s surface temperature from 4.4 billion years ago was under 200ºC, which the authors take to mean that any Giant Impact must have happened before then; but they question whether there was such a putative Giant Impact and note that a capture of the Moon would not have affected Earth’s surface temperature.17

This explanation of the origin of the Moon also provides a solution to the lunar inclination problem: the high obliquity of the Moon’s orbit (5.1°) is in the vicinity of the obliquity of Mercury’s orbit (7.0°), and it is higher than the obliquities of the orbits of the other planets.

Comets Earth and Mars

According to OSSO, Jupiter’s gravitational field would also have pulled the Earth into the inner solar system. Tidal heating caused by passing Jupiter would account for evidence that the Earth’s surface once had a magma ocean, and shedding of surface materials and loss of a primitive atmosphere would have created a cometary tail. As with Moon and Mercury, it appears that Mars and the Earth originally formed a single protoplanet (“Terramars”), and the immense gravitational field of Jupiter pulled Mars out of the Earth (forming the Pacific Basin) as the protoplanet passed by.

heating caused by passing Jupiter would account for evidence that the Earth’s surface once had a magma ocean, and shedding of surface materials and loss of a primitive atmosphere would have created a cometary tail. As with Moon and Mercury, it appears that Mars and the Earth originally formed a single protoplanet (“Terramars”), and the immense gravitational field of Jupiter pulled Mars out of the Earth (forming the Pacific Basin) as the protoplanet passed by.

Here are reasons to think that this is in fact correct: 1) Mars resembled Earth in originally having a great deal of water; 2) the higher density of the Earth would be consistent with a larger body from which the smaller, less dense Mars was extracted in a separation event, on the analogy with Mercury and the Moon; 3) the 9.5:1 ratio of mass between Earth and Mars is likewise consistent with such an extraction; 4) the diameter of Mars, 6792 km, is roughly consistent with the distance across the Pacific between San Francisco and Tokyo, 8266 km; 5) Mars’ north pole is surrounded by circular scarring, suggesting that it was the last part of Mars attached to Earth’s Pacific Basin as Terramars was torn apart by Jupiter’s gravity; 6) circular scarring also surrounds the south pole, suggestive of antipodal disruption, as in Mercury’s south pole; and 7) the sharp difference between the northern and southern hemispheres of Mars would have arisen from a separation event that left the northern hemisphere crust thin and vulnerable to subsequent remodeling by flood basalts provoked by other causes, though a later giant impact18 also played a major role in shaping the northern hemisphere. The extreme extent of the Borealis planitia, its irregular, non-elliptical shape, and the 2-3 km scarp that surrounds it are signs of such a pre-impact birth scar from a separation event, fittingly all on the opposite side of the planet from the tidal bulge of the southern highlands, which is not accounted for by the giant impact alone.

The remanent magnetization in banded stripes of alternating polarity in Mars’ southern hemisphere is reminiscent of the magnetization of the spreading zones beneath the Earth’s oceans and indicative of a powerful, dynamo-driven alternating dipole magnetic field. It represents an outstanding anomaly in a Mars that lacks a dynamo and has only a tiny, non-dipole magnetic field. In the context of OSSO, however, it can be interpreted as having been formed by the original magnetic field of Terramars.

The catastrophic separation while passing Jupiter and the interaction with the giant planet’s immense gravitational and magnetic fields diminished the dynamo in Earth while greatly reducing any dynamo in Mars. In turn, this suggests that Earth’s plate tectonics and geomagnetic field go back to Terramars. Since weathering and plate tectonics have destroyed any evidence of the original surface of the Earth, Mars’ southern hemisphere, though heavily bombarded, contains the only remaining original surface of Terramars. In contrast to Mercury and the Moon, the bombardment of the southern hemisphere of Mars began at the time it was separated from Earth approximately 4.47 billion years ago19. Mars appears to have maintained an eccentric orbit that carried it repeatedly through the asteroid belt for a long time, perhaps until 3.8-3.7 billion years ago, accounting for the heavy cratering in its southern hemisphere and the late formation of the Hellas Basin. As with Mercury and the Moon, this renders unnecessary the Late Heavy Bombardment hypothesis. Then Mars’ orbit became less eccentric.

In an early version of the old, generally discredited fission theory of the origin of the Earth-Moon system, the Pacific Basin was a scar left over from the separation of the Moon from a rapidly rotating Earth. But according to OSSO, the center of the geomagnetic field, roughly modeled as if a bar magnet dipole were buried inside the Earth, is displaced 498 km off Earth’s center of figure in the direction of the Pacific Basin at 25º N, 153º E because Mars was separated from Earth there as Terramars passed Jupiter. Not only the skew of the geomagnetic field but also the Pacific Basin itself and the Hawaiian and South Pacific hotspots are physical leftovers from the separation of Mars from Earth. Much evidence supports this, including the Ring of Fire of seismic and volcanic activity approximately surrounding the crudely circular, appropriately sized Pacific and the thinner (by 2 km) crust of the Pacific compared to the Atlantic crust.

Another leftover of the separation at the Pacific Basin is the South Atlantic Magnetic Anomaly on the opposite side of the world whereby the Van Allen radiation belt comes close to Earth as a consequence of the skew in the geomagnetic field. Arguably, the antipodal disruption caused by the emergence of Mars from the North Pacific also explains Africa’s rich deposits of exotic minerals, above all its kimberlite pipes with their diamonds.

Given the long, tangled history of plate tectonics, continental drift, and other intervening phenomena, the present-day Pacific Basin has changed considerably since its origin in the primeval Panthalassic Ocean, itself a descendant of the original Mirovia Ocean. Still, seismic anisotropy reveals a unique pancake-like pattern at 160 km depth, approximately centered on the island of Hawaii,20 though Mars’ emergence was not necessarily centered on the Hawaiian hotspot, and it seems to have left an oval wound extending into the South Pacific with its hotspots and anomalies. The Andesite Line divides the surrounding andesite crustal rocks from the mantle rocks pulled to the surface of the Central Pacific Basin during the separation of Mars. We may suppose that a similar line could be drawn around the Pacific Basin’s analogue: the low-lying northern lava plains of Mercury.

The emergence of Mars was also the origin of the distinction between the oceanic and continental hemispheres discussed by Peter Warlow21 and divided by a secondary equator that served as an alternative to the standard equator in some episodes of True Polar Wander and inversions. As Earth shrank with the withdrawal of Mars, its surface is likely to have wrinkled, with long scarps analogous to those of Mercury; but weathering and plate tectonics appear to have obliterated them.

The immense heat generated by the Earth’s peripheral passage of Jupiter was stored throughout its mass; this could explain why the Earth’s surface remained warm enough for water during its early years even though the Sun shone at only about 70% of its present output (the Faint Young Sun Paradox).

Are there other candidate dates than 4.47 BYA for the separation of Earth and Mars? Proponents of the Giant Impact theory of the formation of the Moon have found evidence that various asteroids were all struck by fragments that appear to have come from a great cataclysm around 105 million years after the beginning of the solar system 4.6 billion years ago.22 They consider this cataclysm to be their Giant Impact, but according to OSSO that never occurred. At any rate, this very early date seems much less likely than 4.47 BYA for the separation of Earth and Mars.

A separation of Earth and Mars would reduce the number of Peripheral Passages of Jupiter, thus in a sense simplifying the entire OSSO theory. In two cases (Merculuna and Terramars), a separation event occurred. In the third one (Venus), the pull of Jupiter’s gravity caused an elongation of the planet into an ovoid shape, as depicted in ancient iconography, suggesting that Venus, too, had been very close to experiencing its own separation event while passing Jupiter—i.e., that stretching to the point of separation was a normal process during a Peripheral Passage of Jupiter. Just three instances in 4.5 billion years help overcome the objection that it was very unlikely that Jupiter would throw the planets into exactly the right direction to enter the inner solar system (without hitting the Sun) instead of dispatching them to the far reaches of the solar system. These were appropriately rare events.

While each of the terrestrial planets underwent unique experiences following the Peripheral Passage of Jupiter, in terms of axial tilt Mercury (0.01°) is closest to the Moon (1.54°) and the axial tilt of Earth (23.4°) is close to that of Mars (25.19°). In terms of orbital inclination to the ecliptic, again Mercury (7.01°) and the Moon (5.145°) form a fairly close match, as do Earth (0°) and Mars (1.85°). In general, OSSO provides a simple explanation of the obliquities and orbital inclinations of the terrestrial planets, in contrast to the theory of in situ formation, which requires ad hoc collisions with large objects as accretion came to a close. Meanwhile, Mercury and the Moon have similar Bond albedos (0.068 and 0.11, respectively) and visual geometric albedos (0.142 and 0.12, respectively), consistent with their Merculuna origin. Earth and Mars have similar Bond albedos (0.306 and 0.250, respectively), though their visual geometric albedos differ, perhaps because of extensive clouds, snow, and ice on Earth.

Lopsided

Thus we can explain the remarkable, anomalous lopsidedness of the terrestrial planets as a consequence of Jupiter’s gravitational pull during Peripheral Passages. The southern hemisphere of Mars and the far side of the Moon are both tidal bulges that were pulled out by Jupiter’s gravitational field. On Mars the northern hemisphere crust is 35 km thick while the southern highlands crust is 80 km. On the Moon, the near side crust is 60 km thick while the far side crust is on average up to 100 km thick if the thin crust, resulting from an impact, under the South Pole-Aitken Basin is excluded. The center of mass of Mars is displaced to the north by 3.5 km from the center of figure, while the center of mass of the Moon is displaced 1.68 km +/-50 m toward the nearside from the center of figure. Meanwhile, Mercury has a considerably higher amount of iron in its northern hemisphere than in the south, while both the Earth’s inner core and its center of mass (2.1 km from the center of figure) are asymmetrical. In both cases of separation, the lighter molten rock would have more readily been pulled by Jupiter’s gravity into the tidal bulges.

We can expect that the larger partner planet emerging from the separation would have a higher density, being more resistant to the tidal force from Jupiter than the smaller one; and this is indeed the case: the uncompressed density of Mercury is 5.3 grams per cm³ while that of the Moon is 3.3, and the density of the Earth is 4.4 while that of Mars is 3.7. Venus has an uncompressed density of 4.3, which is in line with that of the Earth; and the density of Venus is situated between the densities of Mercury and the Moon.23

In other words, crustal thickness, displacement of center of mass, and uncompressed density of the terrestrial planets all are consistent with being the consequences of a Peripheral Passage of Jupiter.

One can predict that a similar distribution of elements, from light to heavy across the planet, will be found on Venus. Tidal locking, as noted above, caused the anomalous very slow, retrograde rotation of Venus as well as the discrepancy between its center of figure and its center of mass. At 0.28 km, this distance is smaller than those of the other terrestrial planets, but it is much larger than expected error. It seems logical that the stretching of Venus during partial tidal locking would leave a distinguishable yet less prominent lopsidedness than in the planets that were torn in two. Meanwhile, Venus’ perfectly spheroidal shape, evidently the result of remodeling since its pronounced ovoid appearance in ancient iconography, also makes it an outlier: there is no sign of oblateness.

In contrast to the other two Peripheral Passages of Jupiter in OSSO, the Peripheral Passage of Venus around 2525 BC was observed by at least one Greek eyewitness and was recorded in the easy-to-interpret myths of Metis and the birth of Athena. Although Immanuel Velikovsky incorrectly assumed that Venus had emerged from Jupiter itself and that it had approached Earth around 1500 BC, his account of the subsequent interactions of Comet Venus with Earth contains a great deal of evidence regarding the later stages of an OSSO event as observed by human eyewitnesses.

Conclusion

OSSO must lead us to revise current views on:

1. the importance of impacts. They clearly played a significant role but not so dominant a one as has been supposed. Close encounters have shaped the inner solar system in fundamental ways;

2. the presence of dust and gas in the early inner solar system. It appears that, while larger dust particles spiraled into the Sun from Poynting-Robertson drag and other kinds of drag, radiation pressure and the solar wind rapidly pushed tiny particles and gas out to or beyond the asteroid belt or beyond the “snow line” (4.5 AU). There was no need for an anomalous very rapid accretion of the terrestrial planets before the inner solar system was cleared of dust and gas24 because they formed in the outer solar system. Nor, for the same reason, are the low mass of Mars and the main asteroid belt anomalous compared to the mass of Venus and Earth.25 Meanwhile, evidence for the recent finding that asteroids of the CL chondrite class were the source of Earth’s volatiles can be reinterpreted to mean that CL chondrites and Earth originated in the same region of the solar system.26 In effect, the area around Saturn and somewhat beyond Saturn’s orbit was the birthplace of the planets, from which some of them wandered outward from the Sun while others were pulled inward;

3. the origin of water on the terrestrial planets. OSSO provides a simple explanation;

4. the hypothetical Late Heavy Bombardment, which never happened;

5. the Giant Impact hypothesis of the formation of the Earth-Moon system, which is incorrect. OSSO provides superior explanations of the Moon’s heavily cratered surface, the near side/far side dichotomy (including surface features and crustal depths), the complementary low iron of the Moon and high iron of Mercury, the lunar magnetic field, Oceanus Procellarum, lunar melt inclusions, the displacement of the center of mass of the Moon, thermal layering, and an orbit that shows high past eccentricity;

6. the origin of the Pacific Basin, the seismic anomalies beneath it, the Andesite Line, and the Ring of Fire that surrounds it;

7. key features of Mercury;

8. Mars, once part of our planet; and

9. Venus. OSSO offers evidence and explanations that make more believable the mythical accounts of the ancients27 and, following them and much other evidence, the interpretation of Immanuel Velikovsky that Venus emerged from (in fact, passed close to) Jupiter and entered the inner solar system during the Bronze Age. It provides simple, parsimonious, highly appropriate solutions to otherwise poorly explained anomalies of Venus, including the outstanding anomaly of its slow retrograde (but swiftly turning prograde) rotation.

*****

Kenneth J. Dillon is an historian who writes on science, medicine, and history. For planetary and Earth science related to OSSO, see his The Knowable Past (2nd edition, Washington, D.C.: Scientia Press, 2019). See also the biosketch at About Us.